A tad nippy out there today. The weather networks say it’s only -10°C but my body says they are messing with my mind. This brings me to note that my mind is very messy these days. We’ve just ended the lease on our office in the city and will be working from home for the remainder of our debt load reduction. That may take a generation. It’s hard letting go of 25 years in one place, meeting and sharing the sorrows and joys of everyday life. I’m practising it as preparation for that final letting go. Grief, not for the object lost but as an adjustment to new surroundings.

Thankfully practice has been a buoy in both these calm and turbulent mental states. But practice has fallen off the edge since Pandemic 1.0 began and I’m becoming aware that I’m immensely talented at avoiding the cushion because it holds far more than my well-padded butt. Another awareness is a seed I planted about a year ago about exploring the intersection of the core suttas and their impact on my life. No, not a biography; more a series of prompts – the suttas and/or the events – to dig deeper into skillful practice.

It’s also a commitment to write, to breathe, to open the hand of thought and release clinging to that single moment when all will happen the way I want it to.

In a recent interview with a cherished colleague, I was asked how I came to the space of advocating for ethics in mindfulness based psychological interventions. What was the path that made this aspect of mindfulness so important to me that I would devote my work and practice to it? The question woke up deep memories of the people in my life who planted and cultivated the seeds of the Buddhadhamma and how they lived sila.

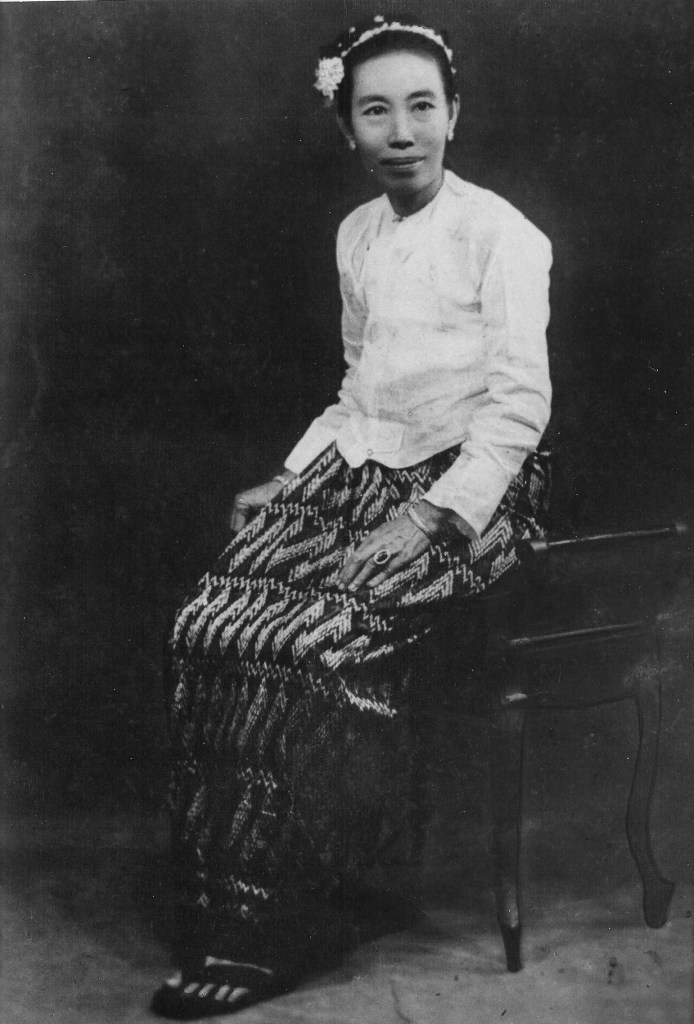

This is my grandmother. Daw Khin Myaing. A devout Buddhist who was also a cheroot-toting, wooden slipper-slinging mother of a wild band of children including my father. She was horrified by my parents’ Sunday afternoon poker parties and would sweep me off to Botatung pagoda. There, we would feed the turtles and chant the suttas with the monastics. A powerful seed that began to sprout decades later when, in stressful moments, I would hear the chants as an inner voice. But this was so long after we had immigrated that they were merely syllables with no meaning.

More years passed until out of curiosity – and a bit of anxiety that I was “hearing voices” – I discovered what they were:

Buddham saranam gacchami

I go to the Buddha for refuge.

Dhammam saranam gacchami

I go to the Dhamma for refuge.

Sangham saranam gacchami

I go to the Sangha for refuge.

The lineage from the Buddha to my grandmother is unbroken, as it remains unbroken for all of us who remember what our commitments are.

Wake up and all beings awake with you.

The next few posts will explore the key suttas (sutras, stories) that have enriched my life practice (hopefully but no promises!). I hope you join me in this exploration of living skillfully in difficult times.